Giuseppe Di Vittorio drew the curtains and turned on the large chandelier, two of whose bulbs were out. The drafts from the windows let in the bitter cold of that evening in December 1938. The meeting room at the Italian Communists’ exile HQ in Paris soon filled up.

First to arrive was Ethiopia’s representative to the League of Nations, Lorenzo Taezaz. Then there was a large and noisy French delegation: Georges Mandel, recently appointed Minister of the Colonies; his chief of staff, André Diethelm; the Radical Party’s Pierre Cot, a politician who had good relations with Communist organizations and had been trade minister in the second Popular Front government; and Colonel Paul Robert Monnier of the Deuxième Bureau, France’s military intelligence service.

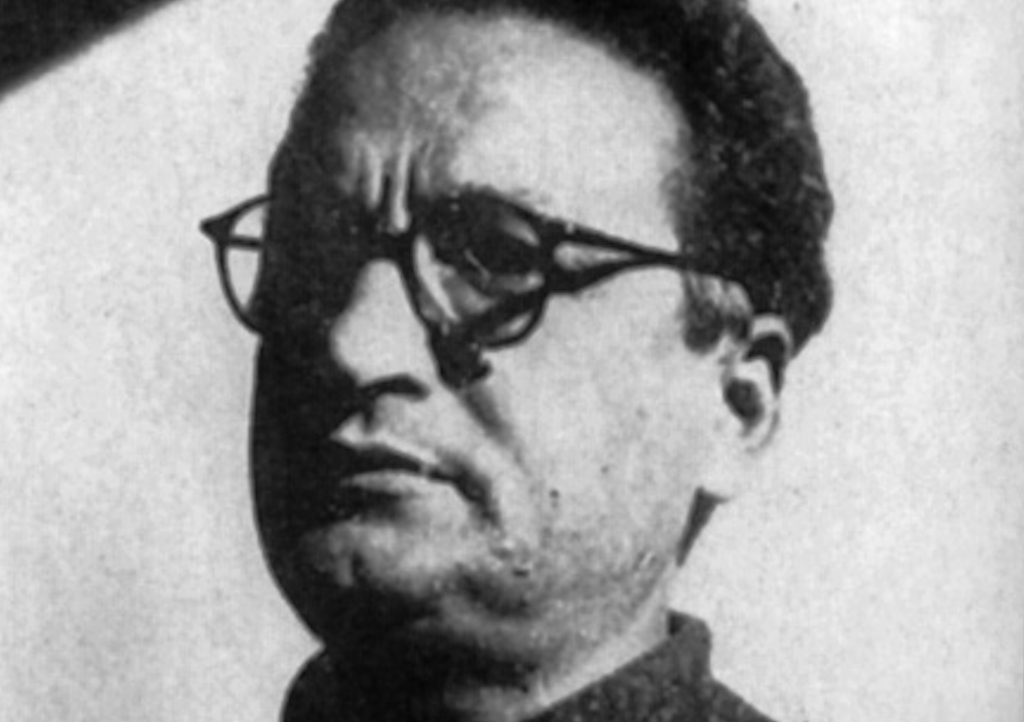

In front of the other Communist leaders, Di Vittorio outlined the mission headed for Ethiopia. He said that he had recruited a dozen experts during his time in Spain, but that three or four fighters would be setting off for Ethiopia.

The militants who Di Vittorio chose were surely plucky, but also men of inventiveness and imagination. They were the type able to get themselves out of tricky situations — and to cope with a hostile and treacherous environment. The three militants chosen were Ilio Barontini, a veteran of the Spanish Civil War; Anton Ukmar; and Domenico Bruno Rolla, who had been involved in the painful retreat from Spain. Mandel said he was willing to make available all the channels Paris had open with the Ethiopian resistance. Colonel Monnier confirmed that the Deuxième Bureau and even the British stationed in Sudan had already established direct contacts with the Ethiopian ras (chief, or duke) Kassa Haile Darge and Abebe Aregai.

…

Auteur: Marco Ferrari