From Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World to Dexter’s Laboratory cartoon series, sleep-learning has been a recurring theme in fiction. The idea that we can learn while asleep has fascinated many, but whether it is sheer fantasy or scientifically possible has long remained a mystery.

Now, thanks to neuroimaging, we know that the brain is far from inactive while we sleep and continually reacts to information from the world around it. But can it really memorise this information and retain it once we are awake?

In fact, we have known for close to a decade that the brain is capable of taking in new information during sleep, as first evidenced in experiments on tone and odour associations.

Individuals who wished to quit smoking, for instance, have been found to reduce their consumption by 35% when the scent of tobacco is presented to them during sleep in association with unpleasant scents of rotten fish.

We thus set out to understand whether the brain was capable of more complex learning processes, such as those involved in foreign language acquisition. Together with Sid Kouider at the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) – Paris Science et Lettres (PSL), and Maxime Elbaz and Damien Léger of the Paris Hospitals Public Trust (AP-HP) Hôtel-Dieu, we designed a protocol for learning the meaning of Japanese words while asleep.

Learn Japanese while you sleep

The Japanese language has a relatively simple structure with a limited number of possible syllable units. For example, the word neko, meaning “cat”, comprises two units: ne and ko. It does not contain a complex tone system like other East Asian languages, and presents a somewhat similar phonology to that of French or English.

However, word meaning is often very distant from French or English. As such, Japanese was the ideal language for the experiment, since the subjects’ ears would be able to distinguish its sounds easily, but the words would generally be meaningless to them.

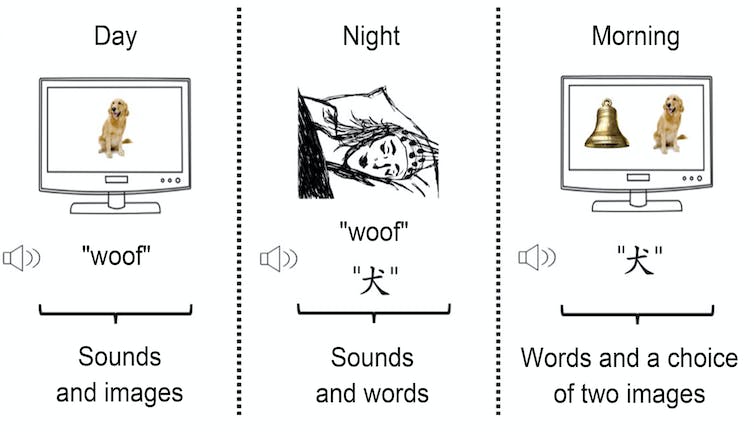

After designing our experiment, we recruited 22 healthy adults who had no prior knowledge of Japanese or other related East Asian languages. As shown in the illustration below, we first presented them with pairs of sounds and images while they were awake, such as a dog with a barking sound. Then, while the subjects were sleeping, we played the sound together with the corresponding term in Japanese.

For example, the barking sound would be played along with the word inu, meaning “dog”. The following morning, we asked the subjects to pick between two images to find the matching word in Japanese. Here, the word inu would be shown along with the image of a dog and the image of an unrelated word that was played while the subject slept, for example, a bell.

In our study, we played Japanese words along with different sounds while the subjects were sleeping – for example, the sound of a dog barking for the word inu, meaning ‘dog’. The following morning,…

La suite est à lire sur: theconversation.com

Auteur: Matthieu Koroma, FNRS Postdoctoral Researcher, Université de Liège