Vitor Alves stops his four-wheeler along the road that leads to Cuito Cuanavale. The town in Angola’s southeastern corner has often been dubbed “Africa’s Stalingrad” due to its longtime besiegement (October 1987–June 1988) during the civil war that gripped the country throughout the final quarter of the last century. He points to abandoned and dilapidated tanks, adorned with graffiti and looted of technical gadgets, decorative items, and removable scrap metals.

“Be careful, there’re still landmines here,” Alves warns. Despite a massive nationwide cleanup effort, over a thousand minefields across Angola must still be cleared.

Alves was the son of Portuguese settlers who escaped dire poverty in their homeland under António Salazar’s fascist Estado Novo dictatorship. Born in a newly independent African nation that had suffered five hundred years of colonialism, he recalls a violent youth.

“Angola’s birth was more a Big Bang than a blank page,” he says while studying the dusty and desolate landscape that was center stage during the civil war. “The Alvor Agreement,” he sighs. “What a shit piece of work!”

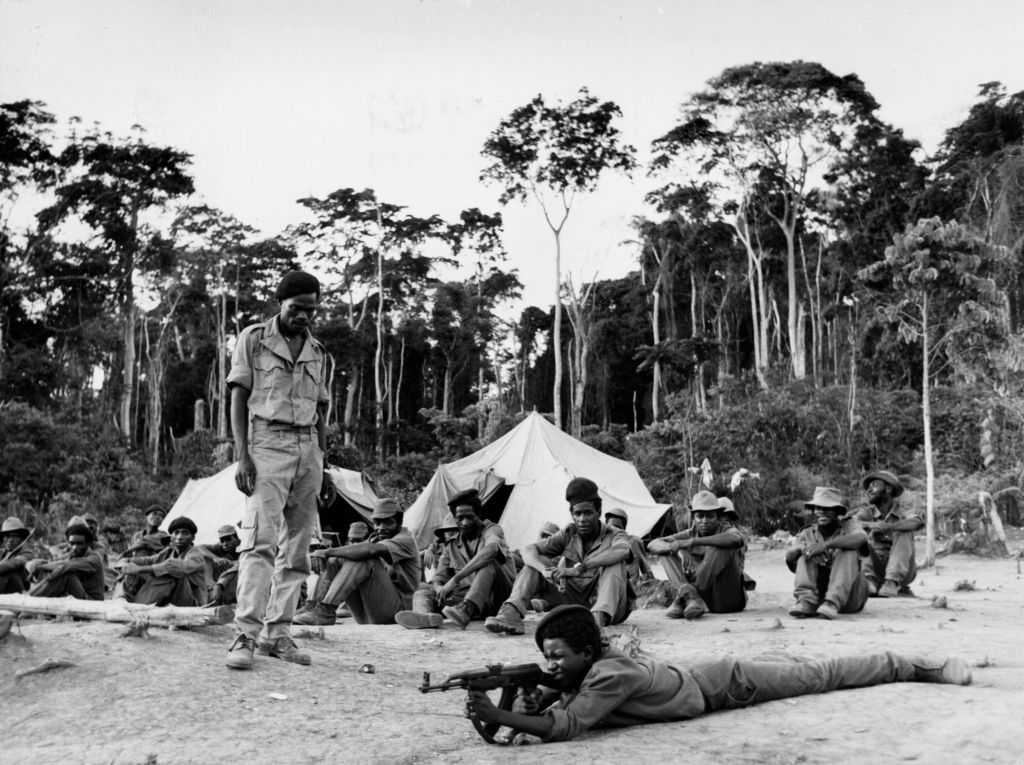

The ten-page document, signed on January 15, 1975, by Portugal and Angola’s three liberation movements, promised the start of a bright future. Army captains disillusioned by the failures of Portugal’s brutal warfare in the African colonies — Mozambique, Portuguese Guinea, and Angola — had overthrown the dictatorship in Lisbon during the Carnation Revolution in late April 1974, thus ending four decades of fascist rule and five centuries of colonialism.

Even as Europe’s last colonial empire was being hastily dismantled, the US Army bombed with impunity in Vietnam and Cambodia amid an oil crisis that had…

Auteur: Klas Lundström