August 22, 2022. Kongsvegen glacier, 20 km west of Ny Ålesund, Svalbard archipelago, Norway.

This is it, we have reached the bottom of the glacier. It is 327m under our feet. After drilling into the ice for six hours, our hot-water jet blasts into the sediment. The hose that connects it to the surface stops rolling and Thomas Schuler, the project leader, confirms that the base has been reached.

I get off the helicopter and Coline Bouchayer, a PhD researcher overseeing the project, tells me the good news. We let out a sigh of relief – John Hult, the project engineer, and Svein Oland, a mechanic from the Norwegian Polar Institute, are particularly content. We had tried to carry out the same operation last spring, but the -30°C temperatures froze the water in the drilling system, making it impossible to continue. This time, the engines that are still running bring a smell of diesel to the frozen lands around us.

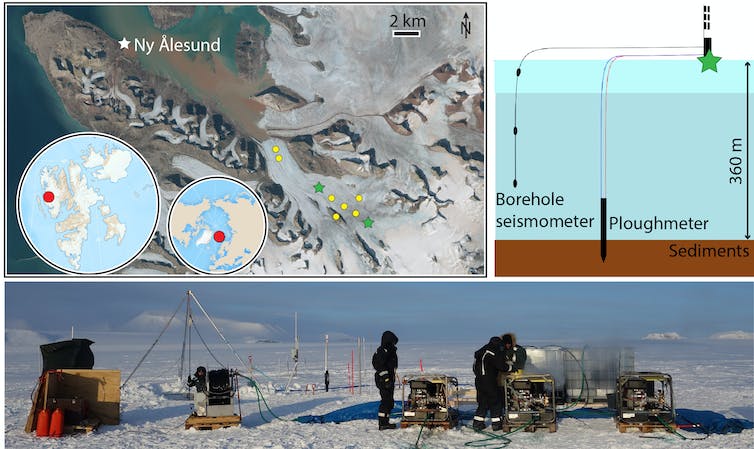

Kongsvegen, the Arctic glacier in Svalbard where we carried out our research. To find out what lies hundreds of metres below, we drilled down to the sediments beneath the glacier (see green stars). There, we installed a ploughmeter to measure the forces at the base of the glacier, and several seismometers to ‘listen’ to the vibrations of the glacier. We also put up seismometers at various locations (yellow dots) on the surface of the glacier.

T.V. Schuler

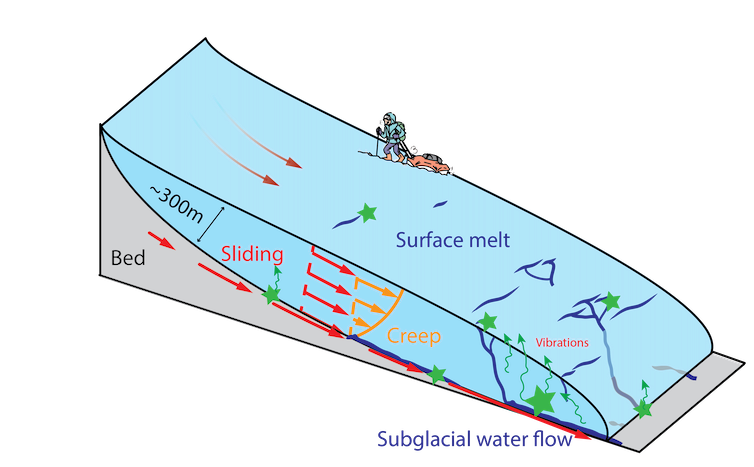

Our goal here is not to reconstruct past climates by extracting ice cores like missions in Antarctica or Greenland. Instead, it is to explore what happens hundreds of metres below the surface, where the glacier rests on its bed of rocks and sediment. This is where their stability is at stake, as liquid water from the surface seeps in and acts as a lubricant.

Rapidly rising temperatures brought on by climate change are set to melt glaciers and trigger instabilities, as predicted by the Intergovernmmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Current policies are projected to result in about 2.7°C warming above pre-industrial levels by 2100, way above the 1.5°C maximum recommended limit by the Paris agreement. Such differences can be drastic for glaciers. These ice dragons, which look as if they were asleep, can wake up a little too suddenly, as shown by the recent collapse of glaciers in the Italian Alps.

Glaciers move thanks to the presence of liquid water at the ice-bed interface. Even the slightest movement creates a vibration that can be recorded by our seismometers.

Ugo Nanni, Author provided

The movement of glaciers (from a few metres to several kilometres per year) is similar to that of a soft cheese on a sloping board: they sway over their entire height and creep under their own weight. The steeper and thicker they are (up to several kilometres), the faster they flow to lower altitudes. Thanks to the…

La suite est à lire sur: theconversation.com

Auteur: Ugo Nanni, Research scientist, University of Oslo