Looking back at the films of Cuban director Tomás “Titón” Gutiérrez Alea almost thirty years after his death, the claim can be made that he occupies a unique position for a deeply political filmmaker in a country of political filmmakers, during the heyday of a movement of political filmmaking across the continent — revolutionary, Marxist, anti-imperialist, and iconoclastic — known as the New Latin American Cinema.

What makes his films stand out is the fact that he can never be accused of political rhetoric, or what Cubans call teque, tediously repeated revolutionary-sounding bombast (except when he’s parodying it). As a result, although the politics of Cuban (and Latin American) cinema have evolved far beyond the heady revolutionary militancy of the 1960s and ’70s, Alea remains a touchstone for subsequent generations, whatever their ideological inclinations. It was striking when he died in 1996 to find that even young filmmakers who didn’t share his political values celebrated his memory.

If Titón cannot be mocked, he did his own share of mocking, and several of his films are ironic and satirical social comedies. His first big international success, Death of a Bureaucrat (La muerte de un burócrata, 1966) is about a country that has made a revolution and decided to become socialist. It therefore insists that its bureaucrats provide equal treatment for all, including the dead: a corpse gets itself unburied for the sake of bureaucracy, and then finds that bureaucracy won’t let it be buried again.

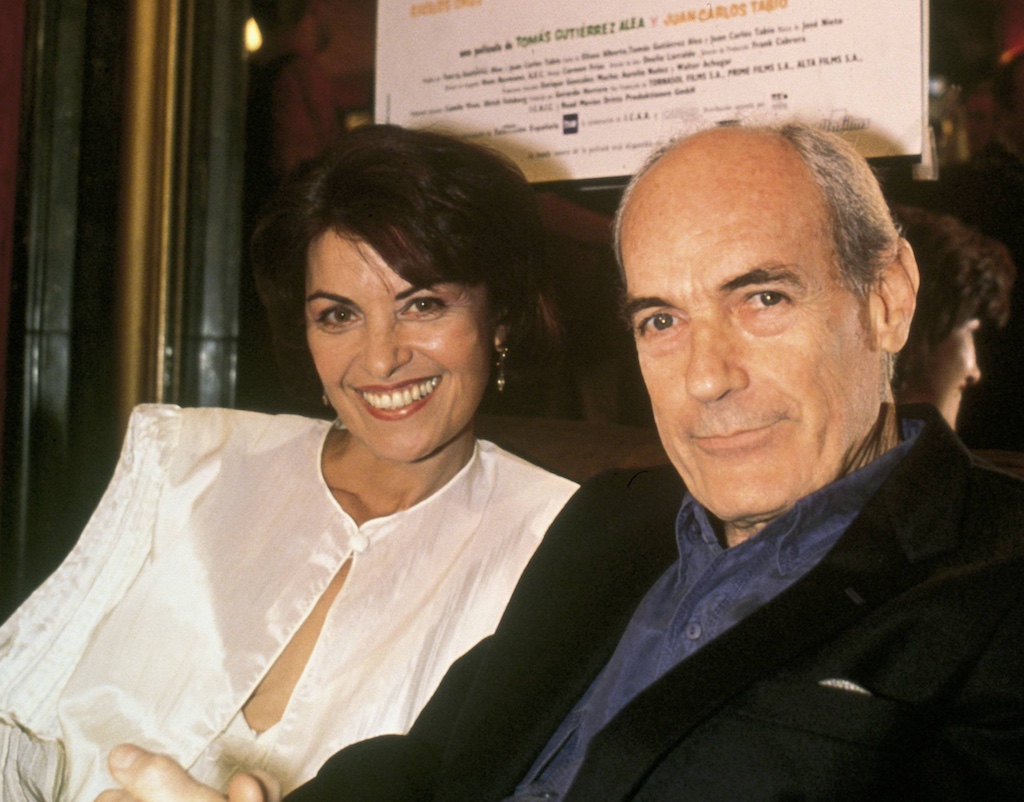

Tomás Gutiérrez Alea remains a…

Auteur: Michael Chanan