As well as being Scotland’s largest city, Glasgow was its industrial heart. Central to the civic story, is the River Clyde, famed as a global shipbuilding hub in the 20th century. But the Clyde, along with an abundant supply of coal, also made Glasgow the ideal location for the textile industry. In the 1820s, spinning mills, weaving mills, dye houses and garment factories sprang up, dominated the urban landscape.

Access to the public sphere and the professional world had been the prerogative of men in the 1800s. But the textile industry presented an opportunity for women. From the introduction of automatic looms and sewing machines, machinery became less physically demanding to operate. That gave women an advantage, and in Glasgow, they began to step out of their homes to claim a place on the factory floor.

Men remained dominant in managerial positions. Women were paid on average between one third and one half of what men earned. In response, Glasgow’s pioneering female workers began a struggle to profoundly change the conditions for women living and working around the world. It would take decades, but they eventually enabled their fellow women to gain visibility and greater rights, both in the workplace and throughout society.

Emily Patmore, 1851, by John Everett Millais.

Wikiart

I have been sifting through research and documents as part of my doctoral studies and they reveal more about the attitudes and barriers these groundbreaking women faced. Such insight into these lives makes their achievements all the more remarkable.

As Glasgow’s textile industry expanded in the 1800s, women represented a rising percentage of the workforce. As the municipal archives show, the city had 403,120 inhabitants in 1861, 58% of whom were women. Of these, 65% were working women, the majority of whom were employed by the textile industries. They came to be seen as a plentiful supply of cheap labour and were, as historian Judith Walkowitz has said, the “symbol of industrial exploitation”.

Factory work and sexuality

The association of women and machines was in itself controversial and prompted a fierce debate. As women shifted into factory work, they were forced to use looms and other machines for up to 12 hours a day, with repetitive gestures. They became, in the eyes of the male supervisors and foremen, “machine women”, bewitched and disembodied. And when femininity was associated to this strangeness, it elicited fear in men. The men came to think of themselves as inquisitors and the machine became the pillory, with women condemned to subordination.

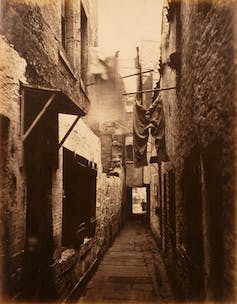

Saltmarket, 1866: working-class living conditions in Glasgow were considered the worst in the UK.

Thomas Annan

These automaton women still possessed a glimmer of humanity, as men in power at the time saw it: their sexuality. For…

La suite est à lire sur: theconversation.com

Auteur: Fanette Pradon, doctorante en civilisation britannique, Université Grenoble Alpes (UGA)